Hampton University Archaeological Project: A Report on the Findings

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0358

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1996

Colonial Williamsburg Archaeological Reports

Hampton University Archaeological Project:

A Report on the Findings

Hampton University

Archaeological Project:

A Report on the Findings

The Department of Archaeological Research

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

Submitted to:

William R. Harvey, President

Hampton University

July 1989

Re-issued June 2001

Report Production

| Project Director: | Marley R. Brown III |

|---|---|

| Project Archaeologist: | Thomas F. Higgins III |

| Contributing Authors: | Andrew C. Edwards |

| William E. Pittman | |

| Gregory J. Brown | |

| Mary Ellen N. Hodges | |

| Marley R. Brown III | |

| Susan R. Alexandrowicz | |

| Eric E. Voigt | |

| Amy Kowalski | |

| Judy Ridner | |

| Consultants: | Cary Carson |

| Fraser Neiman | |

| Ivor Noël Hume | |

| Drafting: | Kimberly A. Wagner |

| Lucia Vinciguerra | |

| Photography/Layout: | Tamera A. Mams |

| Technical Editor: | Gregory J. Brown |

| Technical Assistance: | Shelly Liebler |

| (2001 Reprinting) | Ron Lippert |

This report replaces the first printing in 1989, which included all of the text and graphics following in Volume 1, and a roughly 1000-page artifact inventory in Volume 2. This inventory has not been reprinted, but is available on CD from the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

| Page | |

| Report Production | i |

| List of Figures | v |

| List of Photographs | vii |

| List of Tables | ix |

| Preface | xi |

| Acknowledgments | xiii |

| Chapter 1. Research Design and Management Summary | 1 |

| Chapter 2. Environmental Considerations | 5 |

| Chapter 3. Project Methods | 7 |

| Chapter 4. Historical and Cultural Background | 11 |

| Chapter 5. The Prehistoric Sites (Mary Ellen N. Hodges) | 17 |

| A. Site 44HT36 | 17 |

| B. Site 44HT37 | 27 |

| C. Analysis of Prehistoric Finds | 35 |

| Chapter 6. The Historic Site--44HT55 | 45 |

| A. Description of the Major Features | 45 |

| B. The Structures at HT55 | 71 |

| C. Faunal Analysis (Gregory J. Brown) | 78 |

| D. Oyster Shell Analysis (Susan R. Alexandrowicz) | 95 |

| E. Paleobotanical Report (Eric E. Voigt) | 100 |

| Chapter 7. Artifact Analysis--44HT55 (William E. Pittman) | 113 |

| Chapter 8. Conclusions | 175 |

| A. The Prehistoric Sites | 175 |

| B. The Historic Site | 176 |

| References | 179 |

| Appendices | |

| 1. Muster of 1625 | 195 |

| 2. Catalogs of Tobacco Pipes | 199 |

| 3. Faunal Data | 235 |

| 4. Data Recovery Plan | 247 |

| Page | |

| 1. Context record | 8 |

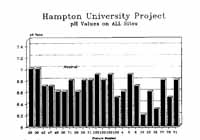

| 2. Soil pH values | 10 |

| 3. Map of area showing conjectural early seventeenth-century property lines | 12 |

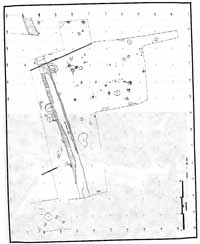

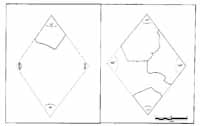

| 4. Overall drawing of 44HT36 | 19 |

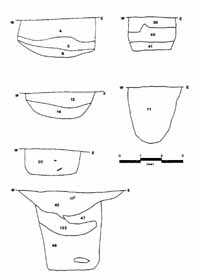

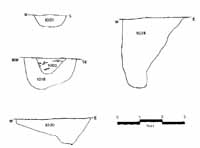

| 5. Feature section drawings—44HT36 | 21 |

| 6. Soil chemistry—44HT36 | 28 |

| 7. Overall drawing of 44HT37 | 30 |

| 8. Feature section drawings—44HT37 | 33 |

| 9. Soil chemistry—44HT37 | 36 |

| 10. Prehistoric pottery—44HT36, 44HT37, and 44HT55 | 39 |

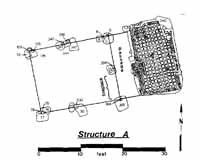

| 11. Detail of Structure A | 46 |

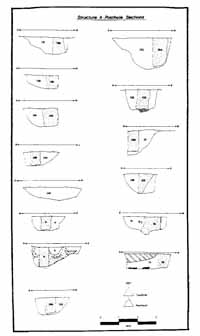

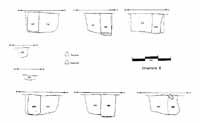

| 12. Posthole sections—Structure A | 47 |

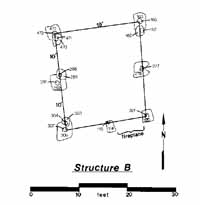

| 13. Detail of Structure B | 49 |

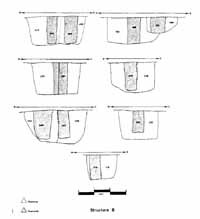

| 14. Posthole sections—Structure B | 50 |

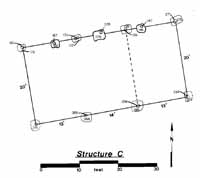

| 15. Detail of Structure C | 52 |

| 16. Posthole Sections—Structure C | 53 |

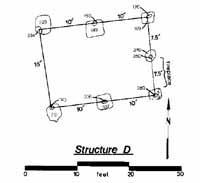

| 17. Detail of Structure D | 54 |

| 18. Posthole sections—Structure D | 54 |

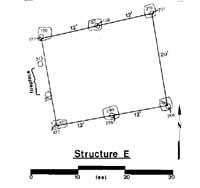

| 19. Detail of Structure E | 56 |

| 20. Posthole sections—Structure E | 56 |

| 21. Detail Plan—Trash Pits A/B | 58 |

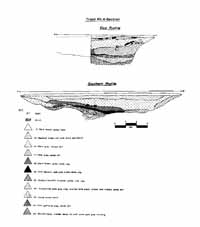

| 22. Section—Trash Pit A | 59 |

| 23. Section—Trash Pit B | 61 |

| 24. Section—Trash Pit C | 62 |

| 25. Section—Trash Pit D | 63 |

| 26. Section—Trash Pit E | 64 |

| 27. Section—ditch feature | 65 |

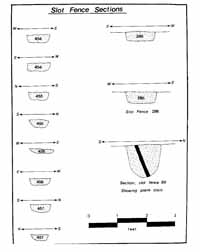

| 28. Overall drawing, 44HT55, showing location of slot fences | 66 |

| 29. Section drawings—slot fence trenches | 67 |

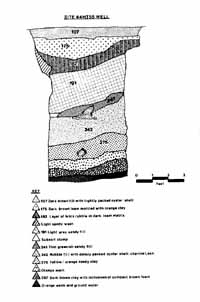

| 30. Section drawing of well | 70 |

| 31. Soil chemistry—44HT55 | 71 |

| 32. Detail plan of Structures A-E | 72 |

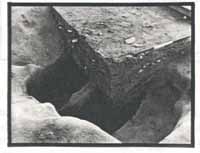

| 33. Detail of cellar wall—Structure A | 75 |

| 34. Detail of cellar steps—Structure A | 76 |

| 35. Detail of cellar floor—Structure A | 76 |

| 36. Kill-off patterns—pig, cow, and sheep/goat | 90 |

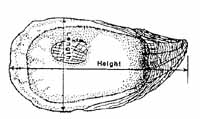

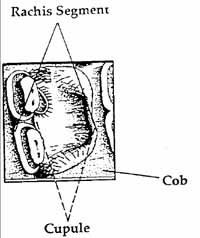

| 37. Oyster shell anatomy | 96 |

| 38. Oyster types and salinity regimes | 97 |

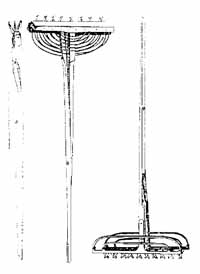

| 39. Oyster tongs | 99 |

| 40. Corn cob morphology | 104 |

| vi | |

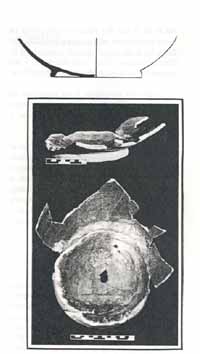

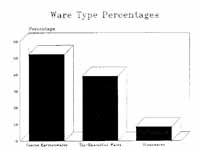

| 41. Percentages of ware types represented | 119 |

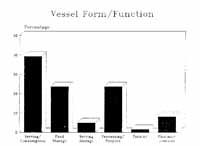

| 42. Vessel form/function | 124 |

| 43. Window pane angles | 140 |

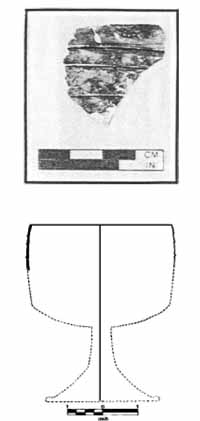

| 44. Drinking beaker foot fragment on projected vessel form | 142 |

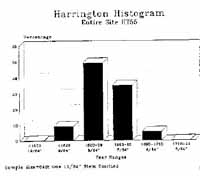

| 45. Harrington histogram—entire site | 148 |

| 46. Harrington histogram—site by feature | 148 |

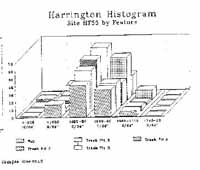

| 47. Harrington histograms—well, Trash Pit A, and Trash Pit B | 149 |

| 48. Harrington histograms—Trash Pit F, Trash Pit H, and Trash Pits F and H combined | 150 |

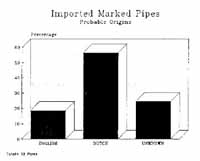

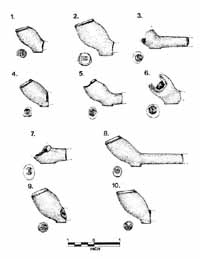

| 49. Imported marked pipes, probable origins | 151 |

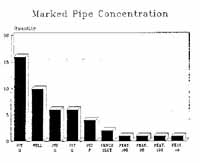

| 50. Marked pipe concentrations | 151 |

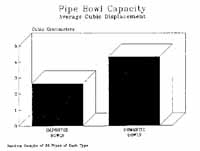

| 51. Pipe bowl capacities—average cubic displacement | 153 |

| 52. Krauwinckel jetton | 168 |

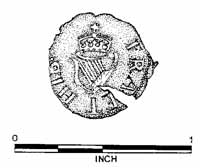

| 53. Harrington farthing, Type 2 | 168 |

| 54. Bale seal | 168 |

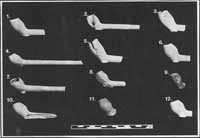

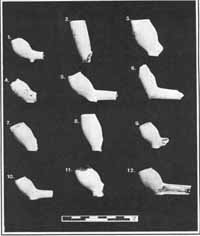

| 55. Dutch pipe | 201 |

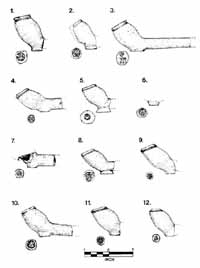

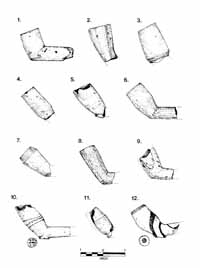

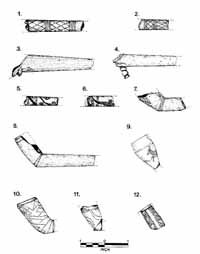

| 56. Imported clay tobacco pipes | 201 |

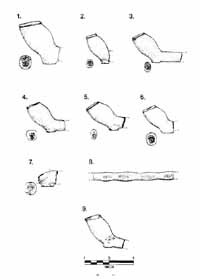

| 57. Imported clay tobacco pipes | 207 |

| 58. Imported clay tobacco pipes | 212 |

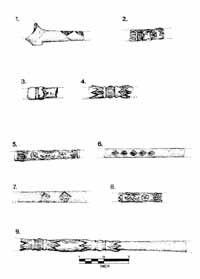

| 59. Decorated imported clay tobacco pipe stems | 224 |

| 60. Domestic clay tobacco pipes | 227 |

| 61. Domestic clay tobacco pipes | 231 |

| Page | |

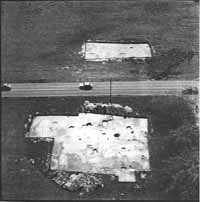

| 1. Aerial view of sites | facing i |

| 2. Aerial view of 44HT36 | 18 |

| 3. Section/excavated plan of Feature 42 | 23 |

| 4. Aerial view of 44HT37 | 29 |

| 5. Detail of human bone in Feature 1001 | 31 |

| 6. Site 44HT36 during excavation | 37 |

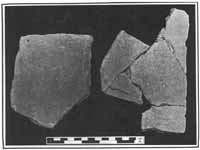

| 7. Examples of Mockley ware | 40 |

| 8. Aerial view of 44HT55 | 45 |

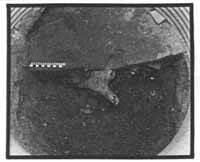

| 9. Quarter-section—Trash Pit B | 60 |

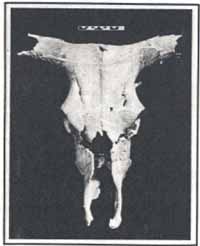

| 10. Detail of cow skull in well | 68 |

| 11. Detail of brick cellar—Structure A | 77 |

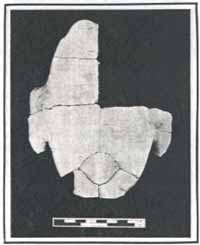

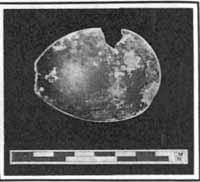

| 12. Turtle plastron | 85 |

| 13. Cut deer antlers | 87 |

| 14. Reconstructed cow skull | 87 |

| 15. Red earthenware strainer, interior and side views with profile | 117 |

| 16. Unglazed earthenware flask, Mexican (?), with profile | 120 |

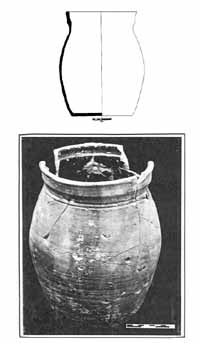

| 17. Thumb-impressed earthenware storage jar, with profile | 125 |

| 18. Red earthenware pipkin handle, with profile | 126 |

| 19. Unglazed pipkin lid, with profile | 126 |

| 20. Locally-made earthenware storage jar, with profile | 128 |

| 21. Iberian oil jar mouth, with profile | 129 |

| 22. French earthenware storage jar, exterior and interior views with profile | 129 |

| 23. North Italian slip marblized porringer handle, with profile | 130 |

| 24. European slipware fragments, with profiles | 131 |

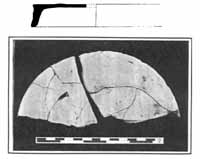

| 25. North Devon slip-sgraffito dish, with profile | 131 |

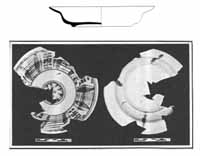

| 26. Portuguese/Spanish majolica plate, interior and exterior views with profile | 132 |

| 27. Portuguese/Spanish plate, interior and exterior views with profile | 133 |

| 28. Portuguese/Spanish majolica plate fragment from the Jamestown Collection | 133 |

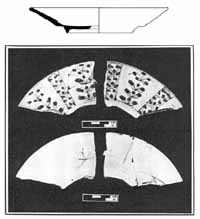

| 29. Portuguese majolica bowl, interior and exterior views with profile | 134 |

| 30. Portuguese majolica bowl rim fragment from the Jamestown Collection | 134 |

| 31. English delftware jug, with profile | 135 |

| 32. English delftware drug jar, with profile | 135 |

| 33. English delftware polychrome platter, interior and exterior views with profile | 136 |

| 34. Dutch delftware dish base, interior and exterior views with profile | 136 |

| 35. Bellarmine jug neck, with profile | 137 |

| 36. Westerwald blue and grey stoneware jug neck fragments, with profile | 138 |

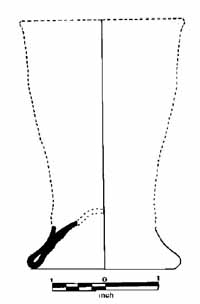

| 37. String-trailed glass container fragment, with profile on projected vessel form | 141 |

| 38. Stemmed wine glass base, with profile | 143 |

| 39. Glass linen smoother handle, with profile on projected form | 143 |

| viii | |

| 40. Spoon bowl with maker's mark | 164 |

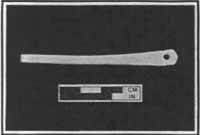

| 41. Bone "needle" | 164 |

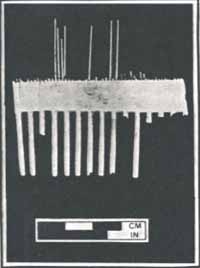

| 42. Bone comb | 166 |

| 43. "Lace" | 166 |

| 44. Lathe-marked plaster | 169 |

| 45. Roofing tile fragments | 169 |

| 46. Overall, structural postholes and cellar of Structure A, ground view | 177 |

| 47. Imported clay tobacco pipes | 216 |

| 48. Imported clay tobacco pipes | 220 |

| Page | |

| 1. Feature Summary—44HT36 | 25 |

| 2. Feature Summary—44HT37 | 32 |

| 3. Prehistoric Ceramic Sherds | 37 |

| 4. Vessel Profiles and Rim Diameters, Mockley Ware | 39 |

| 5. Earthfast Virginia Buildings | 75 |

| 6. Allometric Values | 81 |

| 7. Taxa Identified in the Hampton University Assemblage | 83 |

| 8. Relative Dietary Importance | 88 |

| 9. Estimated Meat Frequencies by Period | 89 |

| 10. Habitat Preferences of Identified Fish | 92 |

| 11. Habitat Preferences of Identified Reptiles/Amphibians | 92 |

| 12. Habitat Preferences of Identified Birds | 93 |

| 13. Habitat Preferences of Identified Mammals | 93 |

| 14. Oyster Shell Attributes by Percentage | 100 |

| 15. Oyster Shell Attributes by Raw Count | 101 |

| 16. Oyster Shell Attributes—Summary | 102 |

| 17. Oyster Shell Size | 102 |

| 18. Botanical Remains in 44HT36 Samples | 107 |

| 19. Botanical Remains in 44HT37 Samples | 108 |

| 20. Botanical Remains in 44HT55 Samples | 109 |

| 21. Ceramic Ware Type Quantification | 118 |

| 22. Ceramic Vessel Form Quantification | 121 |

| 23. Ceramic Vessel Function Quantification | 123 |

| 24. Tobacco Pipe Decorations from 44HT55 | 144 |

| 25. Binford Pipe Stem Dating Calculations | 146 |

| 26. Maker's Marks on Imported Tobacco Pipes | 153 |

| 27. Artifact Function Categories | 156 |

| 28. Summary of Food Preparation and Consumption Items | 170 |

| 29. Summary of Cutlery Items | 170 |

| 30. Summary of Tools and Equipment | 171 |

| 31. Summary of Weaponry and Armor | 171 |

| 32. Summary of Personal Items | 171 |

| 33. Summary of Textile-Related Items | 172 |

| 34. Clothing Pin Distribution | 173 |

| 35. Summary of Trade-Related Artifacts | 173 |

| 36. Summary of Furniture-Related Artifacts | 174 |

| 37. Summary of Architectural Artifacts | 174 |

| 38. NISP, MNI, and Pounds of Usable Meat | 237 |

| 39. Biomass | 240 |

| 40. Age Distribution for Domestic Pig | 243 |

| x | |

| 41. Age Distribution for Domestic Cow | 244 |

| 42. Age Distribution for Domestic Sheep/Goat | 245 |

Preface

In 1979, a plowed field on the Hampton University campus containing site 44HT55 was surveyed by Howard MacCord for the Virginia Department of Highways and Transportation (now the Virginia Department of Transportation). This survey was conducted as part of the examination of the right-of-way for a proposed new extension of state Route 143. MacCord did no excavation, but identified a seventeenth-century domestic site, 44HT55, on the basis of a surface sample of imported and locally-made clay smoking pipes and a few fragments of tin-enamelled earthenware and Rhenish stoneware. Based on this material, MacCord attributed the site to the third quarter of the seventeenth century.

The parcel was again examined in 1980 by Mark Wittkofski, staff archaeologist with the Virginia Division of Historic Landmarks. Wittkofski did some limited subsurface testing in the area of 44HT55, finding two features: a narrow trench identified as support for a paling fence, and another wider trench. Wittkofski concluded that:

A phase three excavation will be required for 44HT55 if it becomes threatened by any construction. Limited testing indicated the site had good preservation of subsurface cultural features. Since much of Hampton has been heavily urbanized, this site could provide important information concerning the changes which took place in the lower Tidewater region (1980:6).

Subsequent construction of the Route 143 extension and interchange did not affect 44HT55, and the site was left undisturbed until the spring of 1987. Knowing of the site's existence, Hampton University officials arranged with the local chapter of the Archaeological Society of Virginia to examine site 44HT55 further and salvage any significant remains prior to the development of a housing complex and shopping center by the university.

The Kicotan Chapter of the A.S.V. began their investigation of the site by digging a number of test trenches in the plowed field. Almost immediately, they encountered a brick-lined cellar. Other trenching activities in the vicinity revealed several features, which, along with the cellar, were partially excavated by the Kicotan Chapter.After these discoveries were made known, university officials sought professional advice. Museum Director Jeanne Zeidler contacted the Tidewater Cultural Resource Center at the College of William and Mary, and the discoveries made by the A.S.V. were reviewed in the field by T.C.R.C. officials. Discussion with Hampton University representatives indicated the possibility of funding through a United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grant to help finance the project. In view of the recommendations made in Wittkofski's 1980 report, the Center suggested a proper Phase II investigation of HT55 be undertaken concurrently with a combined Phase I and II study of the entire development parcel. The T.C.R.C. completed this work in mid-September 1987, as part of a cooperative agreement with the University (see Appendix 4).

Upon completion of the Phase I and II investigations, the university asked the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Archaeological Research to carry out Phase III excavations on the three sites (44HT36, 44HT37, and 44HT55) identified by the T.C.R.C. Field work headed by Thomas F. Higgins III began on October 27, 1987 and was completed in early May 1988. This is a report of those findings.

xiiAcknowledgments

The Hampton University Archaeological Project was successfully completed through the efforts of a great number of interested and dedicated people. The authors would like to thank the following for their contributions:

Hampton University

William Harvey, University President, for his interest and encouragement.

Charles Wooding, University Development Director, for his efforts in coordinating research interests with construction efforts, as well as for his patience and understanding.

Jeanne Zeidler, University Museum Director, who deserves special thanks for her part as liaison between the University and the Foundation, securing space and equipment for the effort, and offering support and encouragement to the archaeological team.

Additionally, the Maintenance and Landscape departments at Hampton University are especially thanked for helping numerous times by providing equipment and supplying needed electricity to the site. The R.O.T.C. Department allowed the field crew to use their facilities and was, thankfully, not too upset about the holes in their parade ground.

We are also grateful to the Audio-Visual Department for loaning us a brand new IBM Model 30 computer for database management.

Department of Historic Landmarks

Tony Opperman and Randy Turner, for their aid and suggestions regarding the interpretation and excavation of the aboriginal sites.

Bruce Larson, for his help in guiding the Foundation and the University through the compliance requisites.

Colonial Williamsburg

The field and laboratory crew who expertly excavated all three sites in spite of a long and cold winter and the sixty-mile round-trip commute:

Thomas Higgins, Project Archaeologist

Lucie Vinciguerra, Field Technician

Charles Thomas, Field Technician

Nathaniel Smith, Field Technician

Meredith Moodey, Field Technician

William Sheppard, Excavator

Gunnar Brockett, Excavator

James Card, Excavator

Amy Kowalski, Laboratory Technician

Judy Ridner, Laboratory Technician

Julie Bledsoe, Laboratory Technician

Walter Schmidt, Laboratory Volunteer

Kathleen Pepper, Laboratory Technician, who supervised the Hampton laboratory activities and offered her help and guidance.

Joanne Bowen Gaynor, who provided general supervision and advice in the faunal analysis.

Nan Reisweber, Department of Archaeological Research secretary, who provided administrative support.

Robert C. Birney, Sr. Vice-President, who approved the project and offered his support.

Cary Carson, Vice-President, Research, who offered administrative support as well as his expertise in seventeenth-century vernacular architecture.

Ivor Noël Hume, Foundation Archaeologist (Retired), who also visited the site, offering his expert advice on both the interpretation of the features and identification of many of the artifacts recovered.

xivRob Hunter, Dave Muraca, and Patricia Samford, who offered their help in the field, pitching in when needed the most.

Dave Doody of the Colonial Williamsburg Audio-visual Department arranged for the helicopter and expertly photographed the sites from the sky.

Tom Olds, who often volunteered his much appreciated efforts, both in the field and laboratory.

Susan Wiard, who contributed her precise and invaluable editorial skills for the artifact analysis section.

Others

Fraser Neiman of Yale University, who provided his expert advice on vernacular architecture.

Professors Norman F. Barka of the College of William and Mary and Jay Custer of the University of Delaware, who likewise gave us the benefit of their expert opinions.

We would also like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of the staff of the Virginia Department of Historic Landmarks in Richmond, the National Park Service facility at Jamestown, and the Departments of Birds and Herpetology of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History for access to their collections for comparative study.

Chapter 1.

Research Design and Management Summary

Site Significance

The development of the area on the Hampton University campus in which the historic and prehistoric sites were located was accomplished, in part, with financial assistance from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). As a result, federal mandates require that the significance of these sites be assessed in terms of the criteria for eligibility to the National Register of Historic Places. For nomination, a site must be:

- A. Associated with significant events in the broad patterns of national history,

- B. Associated with the lives of persons significant in our past,

- C.Representative of a time period, or method of construction, or the work of a master, or

- D.Capable of yielding important information about the past (from Brown and Bragdon 1986:2).

Clearly, all three of the sites take on respective importance primarily in the character and quality of the information they contain. As with most archaeological sites, this information is most directly related to the first and fourth of the National Register criteria. Evaluating the research potential of these sites more specifically is a matter of identifying the relevant historical and cultural patterns and processes to which they relate, and specifying the categories of archaeological data recovered which will help to understand these events and developments. Much of the intellectual and procedural framework for this evaluation is based on a comprehensive historic preservation plan for the James-York peninsula, Toward a Resource Protection Process: Management Plans for James City County, York County, City of Poquoson, and City of Williamsburg, prepared by the Colonial Williamsburg Department of Archaeological Research in 1985 and 1986 (Brown and Bragdon 1986).

The Prehistoric Sites — 44HT36 and 44HT37

Study Unit III in Colonial Williamsburg's 1986 resource protection plan for the Peninsula addresses several research questions pertinent to the investigation of sites 44HT36 and 44HT37. On the basis of radiocarbon analysis and associated diagnostic artifacts, the prehistoric sites at Hampton University can be dated to the latter part of the Middle Woodland Period (500 B.C.- A.D.1000). This traditional chronological unit falls within a broader era of cultural adaptation, spanning the period 2000 B.C. to A.D. 1000, defined in Study Unit III.

Referred to by some as the Woodland I Period (Custer 1984, 1989), this era is distinguished by the emergence of a more sedentary lifeway among the Native American populations of the Peninsula and the larger Middle Atlantic Region, although the exact processes involved with this change remain unclear. Earlier, populations within the region were characterized by forest-based economies, high residential mobility reflecting seasonal resource availability, small group size, and a portable tool assemblage. Beginning ca. 2000 B.C., however, the archaeological record displays evidence for the development of intensive riverine and estaurine adaptations and increased residential permanency by larger group aggregates. Technological innovations through the period included the development a ceramic container technology, the construction of food storage facilities, and the development of plant horticulture. The latter is believed to have initially involved the 2 intensive use of wild, herbaceous annuals, with true domesticates integrated at a later date.

Using guidelines from the management plan, sites 44HT36 and 44HT37 were excavated with the intent of adding to existing knowledge of the social, economic, and demographic organization, subsistence activities, and material culture of Native American peoples during this era. Prior to identification of these specific sites, the Hampton University project area had been judged likely to contain prehistoric archaeological remains due to its topographic setting and proximity to estuarine resources. A previous archaeological survey (Wittkofski 1980) had recovered small surface collections of aboriginal pottery and stone tools in the nearby fields. The first clear indication of the potential prehistoric significance of the area came, however, during Phase I and II testing by the Tidewater Cultural Resource Center in the summer of 1987, when it was discovered that pit features were preserved below the plowzone at sites 44HT36 and 44HT37. The presence of pit features suggested these sites represented residential bases involving the storage of plant foods. A preliminary date for the sites was provided by the recovery of Mockley ware, a shell tempered, cord marked and knotted net impressed ceramic common on late Woodland I Period sites within the Coastal Plain of Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware.

In order to address the specific research questions posed in the management plan, data recovery strategy at 44HT36 and 44HT37 included the excavation of the majority of the pit features exposed at the sites and analysis of their depth, breadth, and contents in order to determine their probable function. Material suitable for radiocarbon analysis was collected to date the occupations and to provide additional information on the occurrence of Mockley ware. Soil samples were collected, treated, and analyzed by a paleoethnobotanist to determine which wild or domesticated plants were used by the inhabitants. Rather than limiting the investigation to the small, non-contiguous test units initiated during the Phase I/II investigation, expansive excavation areas were exposed at each site with the hope of obtaining information on the overall plan and internal structure of the settlements—whether shelters, cooking, and other activity areas existed, and, if so, how they were arranged.

Excavation and analysis of the sites suggested that they represent small, residential bases. Unfortunately, only limited information was generated on the plan of the settlements. Within the excavation area exposed at 44HT37, some clustering of pit features was evident, but no evidence for structures was found at either site. Either none existed, or any evidence had been destroyed by subsequent plowing or landscaping. The extremely small size of the artifact assemblages, which were comprised almost exclusively of ceramic sherds, precluded sound spatial analysis. The excavation, on the other hand, did produce some potentially significant data relevant to an understanding of ceramic and horticultural development during the Middle Woodland Period. Radiocarbon analysis of charcoal associated with ceramics and plant remains from the sites yielded some of the earliest dates yet obtained within the Middle Atlantic Region for shell tempered ceramics (first century A.D.) and for the possible limited cultivation of maize (fourth century A.D.).

The Seventeenth Century

Site—44HT55

Study Unit X in Colonial Williamsburg's resource protection plan, "Establishment of Colonial Society: Development of Tidewater Society and Economy A.D. 1630 - A.D. 1689" outlines "the development of a distinctive Anglo-Virginian lifestyle in response to the conditions of the Chesapeake" (Brown and Derry 1986). During this period, the plantation system emerged, based on the cultivation of tobacco and a reliance upon bound and slave labor. The so-called "operating plan" for this study unit identifies a broad range of property types that should be recoverable as archaeological sites. These include plantations of both large and small planters, tenant farms, public buildings, taverns and other commercial sites. 3 Until recently, however, there has been a bias toward the recording and excavation of domestic sites associated with the planter elite, such as those at Kingsmill and Governor's Land, both in James City County (Brown and Derry 1986).

The Hampton University site is of special importance primarily because, although it was probably occupied by a fairly wealthy or socially-prominent household, it was never, at least in the seventeenth century, part of any large private land holding. It was, in fact, probably tenant land that was not part of any permanent estate until it was patented in 1642. Even then it was not a familial holding, but part of a 116-acre tract which likely included several other similar domestic complexes. Site HT55, in fact, probably because of its association with the large tract patented by the Virginia Company, was part of a rural enclave in what was becoming a relatively urban area (although little of Hampton itself, then only part of Elizabeth City County, ever actually became heavily urbanized). It remained such until acquisition by Hampton University in 1938. Thus the full-scale excavation of the site has afforded archaeologists the opportunity to add significantly to the understanding of the material culture of the English population in second quarter seventeenth-century Virginia.

What, then, are the archaeologically-discernible things which distinguished the landless tenant farmers in the second quarter of the seventeenth century from the landed gentry? Is it their houses and their possessions, or is it something less tangible, such as their political connections, education, or ambition? The architectural ghosts and the rubbish left to posterity at sites from this period do not seem to point to any one factor which would explain or define these historically-known differences. Almost all of the houses built in Tidewater from 1625 to 1650 were relatively small, earthfast structures composed of wood, whether home of lord or laborer. Additionally, some of the same ceramic types found at Jamestown, the core of the elite, and at Causey's Care, on the periphery, were also found at HT55. The artifacts recovered from HT55 seem, in fact, to indicate that the residents of the site had sufficient wherewithal to purchase both ceramics and glassware of a quality suggestive of a high standard of living.

The question of social and economic status of the folks living at 44HT55 can be addressed through a variety of sources, but there are few definitive answers. Since there appears to be no evidence that the property served as a glebe-house for the nearby church, an automatic status indicator, that of the clergy, cannot be assumed, nor can it be used, unfortunately, to seek clues regarding the economic well-being of ministers during Virginia's early period.

Looking for insights into the status of the site's inhabitants through their architecture is also questionable ground on which to tread. As pointed out in Chapter 6, social dichotomies between masters and indentured servants were not as well-defined in the first half of the seventeenth century as they were in the second half. This is reflected in the architecture of the houses as well as in the historical record (Neiman 1980), and even in the general layout of the domestic complex. Servants often lived in virtually the same rooms as their "masters." In the Muster of 1625 (Appendix 1), Robart Thrasher and Roland Williames apparently lived in one house with their servant, John Sacker. John and Elizabeth Haney and Nicolas and Mary Rowe also lived with their servants Thomas Moreland and Ralph Hood, as there is only one house listed in these musters. Neiman (1980) found a reference which, off-handedly, mentions a "Negro" servant sitting and drinking with his mistress, a situation unlikely to arise only fifty years later.

It has been demonstrated by Neiman and Carson that houses built by the elite, or at least the "upper echelon" of society, appear to have been constructed in much the same manner as those belonging to people on the lower end of the economic ladder. Even planters who could probably well afford brick houses, or at least frame houses with brick chimneys, had houses constructed entirely of wood with chimneys of mud. There are notable early seventeenth-century 4 exceptions, of course, such as Piercey's house at Flowerdew Hundred (Barka 1976), which had a brick and stone foundation along with the wooden posts and a large double brick chimney. But this was an exception; the earthfast structures at Kingsmill, Epps Island, Pettus, and Drummond plantations were the norm.

Site HT55 consisted of five seemingly meager structures. Atypical of most post-in-ground dwellings, Structure A contained a tile-floored, brick-lined cellar—not a feature as easily or as cheaply constructed as the more common wood-lined ones. It also sported two sets of brick steps leading into the cellar, although the chimney(s) were constructed of wood and mud. Evidently, safe storage of food, a consumable, was more important to the owner than a more elaborate and attractive house. The house met the needs of the inhabitants for about 30 to 40 years, although extensive repairs were apparently necessary.

Chapter 2.

Environmental Considerations

The Climate

Weather on "the Peninsula," as the area between the York and James Rivers is locally known, is characterized by relatively mild winters and warm summers, but not without extremes on both ends of the thermometer. John Smith accurately described the area's climate in 1624:

The Sommer is hot as in Spaine; the Winter cold as in France or England. The heat of sommer is in June, July, and August, but commonly the coole breeses asswage the vehemency of the heat. The chiefe of winter is halfe December, January, February, and halfe March. The colde is extreame sharpe, but here the Proverb is true, that no extreame long continueth.

The winds here are variable, but like the thunder and lightning to purifie the ayre, I have seldome either seen or heard in Europe. From the Southwest came the greatest gusts with thunder and heat. The Northwest winde is commonly coole and bringeth faire weather with it. From the North is the greatest cold, and from the East and Southeast as from the Barmudas, fogs and raines

(Smith 1624:21).

Captain Smith also describes the quick changes sometimes exhibited in Tidewater weather, a fact to which anyone who has lived in the area for much time can attest. Statistically, however, the peninsula's weather is rather mild, the average July temperature being 77.7°F, and the average in January 40.3°F. Annually, the average is 59.1°F. Summer temperatures can, on occasion reach above 100°, and winter nights plummet to near 0°, but both extremes, especially the latter, are rare. Annual rainfall averages about 42 inches, approximately 8.6 inches of which may be recorded as snow (Virginia Peninsula Industrial Council [V.P.I.C.] 1976).

Resources

Total land area of the peninsula is about 262,400 acres, roughly half of which is forested (much less, of course, in the Hampton area). Forests are primarily composed of pine, oak, and hickory trees. The local ground water is generally acidic and contains high amounts of iron, making it unfit for most purposes. At depths below 200 feet, a high salt content pervades all well water in the Hampton area. All of the surface water around Hampton is quite salty, supporting a great deal of marine life including fish, oysters, clams, and crabs (V.P.I.C. 1976).

Geology

Hampton and the peninsula are located on the very eastern edge of Virginia's Coastal Plain, a geologically-old area primarily composed of "loose, unconsolidated beds of sand, gravel, clay, and marl"(Virginia Governor's Office 1968:30) , below which is Cretaceous and Tertiary sedimentary rock (Andrews 1981). As Hampton is located at the very tip of the peninsula, it is at the lowest elevations (site HT55, for instance, is about 10 feet A.S.L.). On the upper part of the peninsula, near Williamsburg, elevations may be as high as 120 feet A.S.L.

The Hampton University sites are at the mouth of the James River as it empties into the Chesapeake Bay. The Bay, probably the greatest influence on the early adventurers, is still today an extremely important waterway. Affording protection from the sea, as well as a great abundance of marine life, the Chesapeake Bay has an area of 4,300 square miles, a shore line of 4,500 miles, is about 165 miles long, but has an average depth of only 20 feet (Power 1970). The early importance of Hampton is directly related to its strategic location in the part of the Bay across from 6 Norfolk—the entire area composing a commercially-important region known as Hampton Roads.

Chapter 3.

Project Methods

A. Excavation

The Native American Sites

The methods and techniques used to carry out Phase III excavations on the three Hampton University sites were structured to obtain the types of data pertinent to addressing several research questions discussed in Chapter 1. The two Native American sites—44HT36 and 44HT37—provided a unique opportunity to broaden the current knowledge of the material and culture history of aboriginal populations in the Tidewater region during the latter part of the Middle Woodland Period.

Phase I and II test excavations performed by the Tidewater Cultural Resource Center at the College of William and Mary revealed subsurface features with few or no cultural remains in the topsoil overburden. When Colonial Williamsburg began the Phase III study, this overburden was therefore stripped by machine until features were evident. A grid was established over the sites, and the features were subsequently mapped and given appropriate numerical designations. All features were sectioned, either in halves or in quarters, depending upon size. A known percentage of the fill from each feature in excess of 2000 ml was retained for wet-screen, flotation sampling, and chemical analysis. The remainder of the fill was screened through one-quarter inch or one-eighth inch mesh hardware cloth. The carbon samples collected were sent to Beta Analytic Laboratories for radiocarbon dating. Artifacts recovered from the sites were generally transferred to the on-campus laboratory for processing at the end of each work day, but items requiring special treatment could be taken to the lab within minutes of their discovery.

The recording method used on the aboriginal sites was the same as that used on other Colonial Williamsburg sites. Features were given consecutive numerical designations as they were mapped. Layers within the features were given context numbers as they were excavated, and all pertinent information relating to the feature or context was recorded on forms designed for computer entry (see Figure 1). This information was later transferred to computer using dBase III-compatible database management software. Major features were photographed in plan and section.

The Historic Site

Excavation and recording techniques employed at HT55 were essentially identical to those used at the Native American sites. Previous archaeological investigations, years of surface collection, and other considerations prompted the stripping of topsoil and plowzone from the site, exposing the subsurface features. The area was gridded into the customary ten-foot squares in order to facilitate mapping of the large site. Again, features were given sequential numbers as they were mapped. Each unit was mapped on a 1:24 scale, producing a composite site plan. All features were sectioned and a portion of the fill retained for chemical, flotation, and wet screen sampling. Most features were photographed in plan and section.

B. Soil Analysis

Flotation

(Charles Thomas and Lucie Vinciguerra)

Soil samples recovered from the Hampton University sites were transported to the Department of Archaeological Research facilities in Williamsburg for flotation. The flotation device used in processing soil samples consisted of two

main sections. The base was a 15-gallon cylindrical NALGENE tank with two holes drilled

8

Figure 1. Context record.

9

through the wall near the base. One hole was fitted with a plug to serve as a drain for emptying the tank between samples, and the other with an L-shaped length of copper pipe running upward through the bottom of the tank. An adjustable spray nozzle was attached to this pipe.

Figure 1. Context record.

9

through the wall near the base. One hole was fitted with a plug to serve as a drain for emptying the tank between samples, and the other with an L-shaped length of copper pipe running upward through the bottom of the tank. An adjustable spray nozzle was attached to this pipe.

The upper portion of the device was constructed of a 20-quart utility tub, with a shallow, rectangular hole cut near the upper edge, and a broad, flat spout attached. The bottom of the tub was removed and replaced with a 24-by-24 brass mesh cloth (wide diameter: 0.014"), which retained all particles greater than 0.0277" (0.70 mm). The tub was selected to create a snug, water- tight fit when pressed down into the NALGENE tank.

Aluminum baking pans with bottoms removed and replaced with 40-mesh brass wire strainer cloth were used for collection of the floated material. These would collect particles of at least 0.0175" in diameter.

Water was run into the base tank from the bottom until it filled the NALGENE tank and spilled over the spout. Then, at high pressure, a stream of water was directed through the screen to create turbulence. The soil was sprinkled into the sample bucket, the lighter fraction of which was carried away through the spout and into the collecting tray. The sample could be agitated slightly by hand to break up any highly coherent soil, if necessary. The process continued until there was no further suspended material visible in the flow to the collecting tray. The tray was then set aside for air drying while the heavy fraction was retained in the screen fitted in the NALGENE tank. The water was drained and the sample extracted between each process.

This method of collecting flotation samples minimizes the handling of delicate material, which is especially fragile when wet. The standard poppy seed test, i.e., placing 100 poppy seeds in a sample before it is processed and counting them after flotation, produced an average recovery rate of 95.5%. This test was run periodically in order to monitor the conditions of the screens, adhesives, and fittings.

Chemical Analysis

Soil samples taken from the three sites were analyzed by the Virginia Department of Agriculture facility at Blacksburg for the following elements: potassium (K), phosphorus (P), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg). Soil pH and the amount of humus were also measured.

Although the constituent element analysis was very revealing, the latter two tests revealed little of major archaeological interest. All of the samples taken were slightly acidic (Figure 2), both the control samples and those taken from specific features. However, the pH value of the soils is significantly affected by rainwater and modern farming practices, and it is likely that these are the principal factors being measured. The pH value of the soil simply gives an archaeologist an idea of how well some items, such as bone, shell, and metals, will be preserved in the ground. The slightly acidic conditions suggest that all of these materials were adversely affected, but probably not drastically so.

The presence of high levels of potassium in the soils of features is generally an indicator of the presence of wood ash. Phosphorus, on the other hand, seems to indicate the presence of human waste material and is usually extremely high in historic- era privies. High calcium levels are generally indicative of the presence of decaying shell or bone within a feature or layer (Pogue 1989). Large amounts of calcium will remain in the soil after the source has seemingly disappeared. Although the samplers were routinely tested for magnesium, which may be important for the health of some crops, its archaeological significance is yet unknown.

C. Artifact Analysis

Artifacts recovered from the field were brought to the archaeological laboratory established on the Hampton University campus. As quickly as possible, the artifacts were washed according to D.A.R. laboratory standards, dried, sorted into categories, and labeled with site and provenance

10

Figure 2. Soil pH values.

number. Oyster shell and brick fragments were separated, counted, and placed in temporary storage. The oyster shells were later sent to Williamsburg for analysis.1The remainder of artifacts were coded according to type and entered into a custom dBase III-compatible program on an IBM Model 30 microcomputer provided by the University. The processed artifacts were placed in open-rack storage in the laboratory until the analysis was complete. All faunal material was remanded to the Zooarchaeological Laboratory

for analysis, and any artifact in immediate need of conservation was transported to the main lab facility in Williamsburg for treatment.

Figure 2. Soil pH values.

number. Oyster shell and brick fragments were separated, counted, and placed in temporary storage. The oyster shells were later sent to Williamsburg for analysis.1The remainder of artifacts were coded according to type and entered into a custom dBase III-compatible program on an IBM Model 30 microcomputer provided by the University. The processed artifacts were placed in open-rack storage in the laboratory until the analysis was complete. All faunal material was remanded to the Zooarchaeological Laboratory

for analysis, and any artifact in immediate need of conservation was transported to the main lab facility in Williamsburg for treatment.

Ceramics and smoking pipes were crossmended under the supervision of the Collections Supervisor. The smoking pipes and some ceramic vessels were also removed to Williamsburg for analysis. The aboriginal artifacts from all three sites were also transported to the main laboratory for analysis by a prehistoric specialist.

All materials from the sites were returned to the custody of the University Museum at the completion of all reporting activities. Chapter 7 of this report is a full discussion of the artifacts from the historic site. Artifacts from the prehistoric sites are discussed in Chapter 5.

D. Paleobotanical Analysis

This study was assigned to consultant Eric Voigt. His report is included in Chapter 6-E.

E. Faunal Analysis

The zooarchaeological study of site HT55 was conducted by staff archaeologist Gregory J. Brown. His methods are described below; his report is included in Chapter 6-C, with tables and detailed data in Appendix 3. Faunal remains from HT36 and HT37, which were both sparse and badly fragmented, were not analyzed.

Chapter 4.

Historical and Cultural Background

The scope of the historical background of the Hampton, Virginia area will be primarily limited to a discussion of events taking place (and to people living or doing business) on the east side of the Hampton River during the seventeenth century. The domestic complex at HT55, which is the primary focus of this report, was established, inhabited, and abandoned between the third and seventh decades of that century, and little archaeological evidence exists at this site which would add significantly to the interpretation of later periods in Hampton's long history.

The known culture history of the Native American peoples who have lived in the Hampton Roads area, especially during the first half of the first millennium, is necessarily limited by the somewhat meager amount of archaeology done in the immediate vicinity over the past several decades. The sites at Hampton University are, perhaps, best understood within a regional context which would include the Virginia Coastal Plain and the larger Middle Atlantic area.

A more comprehensive, non-site-specific history of the Hampton area can be found through the following sources:

- 1983

- Phase II Archaeological Survey of a Proposed Dredging Site in the Hampton River, Hampton, Virginia. Report prepared by Underwater Archaeological Joint Ventures for Langley and MacDonald, Inc.

- 1907

- Narratives of Early Virginia, 1606-1625. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

- n.d.

- Elizabeth City County, Virginia, 1782-1810. M.A. thesis, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg.

- 1936

- The First Plantation, A History of Hampton and Elizabeth City County, 1607-1887. Hampton.

A. Seventeenth-Century Hampton

Several weeks before Capt. Christopher Newport, Capt. John Smith, George Percy, and their party formally established the English foothold in North America at Jamestown, they were enjoying the hospitality of their new-found (but short-lived) neighbors at Kicotan, an Indian town having "eighteen houses pleasantly seated upon three acres of ground" (Smith 1608). It is believed that Kicotan probably stood in the area presently occupied by the Veterans Administration Hospital. Recognizing the strategic importance of the Kicotan area, especially Point Comfort, from which the mouth of the James River could be guarded against the Spanish threat to the south, a fort (called Fort Algernon) was built there in 1609. Two additional forts, Henry and Charles, were erected at the mouth of the Hampton River on its east and west banks, respectively. Fort Henry probably stood between John's Creek and Strawberry Banks, on the shore of Hampton Roads. The military buildup was effective in more ways than one, as the Indians were driven from Kicotan under orders from Sir Thomas Gates in 1610 (McCartney 1983).

Both Thomas Dale and William Strachey wrote that two to three thousand acres of land had already been cleared by the Indians at Kicotan. Although they were not specific, this land

12

Figure 3. Map of area showing conjectural early seventeenth-century property lines.

was probably located on both sides of the Hampton River. The land on the east side of the river (again about 3000 acres) was designated Company land and used to provide a place for those persons coming to the colony at the Virginia Company's expense. It was also used to house the military contingent protecting the area from enemy attack, be it derived by land or sea (McCartney 1983).

Figure 3. Map of area showing conjectural early seventeenth-century property lines.

was probably located on both sides of the Hampton River. The land on the east side of the river (again about 3000 acres) was designated Company land and used to provide a place for those persons coming to the colony at the Virginia Company's expense. It was also used to house the military contingent protecting the area from enemy attack, be it derived by land or sea (McCartney 1983).

In 1619, at the first meeting of the House of Burgesses, the name of Kicotan was changed to the Corporation of Elizabeth City. At that time, and until 1637, Elizabeth City also included the area now known as Norfolk and Virginia Beach. Elizabeth City was then the most populous of the four corporations. Virginia Company records indicate that 349 persons were living there in early 1624. Over a hundred had died during the difficult years following the Massacre of 1622, even though Elizabeth City had fared well in comparison with other areas.

The Muster of 1625 begins to shed the first light on the specific history of site HT55. It, fortunately, separates those persons living on the west side of the river from those living on the east (see Appendix 1). Unfortunately, it does not indicate the exact location of the homesteads or show how much land was involved in each. It does name names, however; names that can, in some cases, be traced though the patent records to other tracts of land on both sides of the river.

The first surviving mention of a lease or patent on the east side of the Hampton River near HT55 is in a lease of 50 acres to Lt. Thomas Flint on 23 February 1626 (page 77 of the original patent book). It leases the land and houses in the Indian Thicket, an area between two creeks (John's and Jones) which had been occupied by Capt. Whitacre. This was former Company land adjacent to Fort Henry Fields, the present site of the Veterans Administration Hospital. This land is 13 included in Capt. Francis West's muster of 1625. Two patents and two pages later in Patent Book I, 50 acres is leased to Rev. Jonas Stockden, who, in the 1625 muster, is listed as living on the west side of the river. The boundaries of his lease are quite specific: 50 acres on the eastern side of the Southampton River, within the Company's Land at Elizabeth City, abutting on its south side a Creek parting this from the land in occupation of Lt. Flint, commonly called the "Indian Howse Thickett," north on another Creek, west on said river and east on the Maine woods. This was recorded on September 8, 1627 (Nugent 1979).

The next lease listed involving the area near 44HT55 is in Patent Book I, page 90, to Christopher Windmill, Planter, for 60 acres abutting south on the plantation called "Indian Howse Thickett," formerly granted to Lt. Flint. The tract was bounded on the north by the "ground of Jonas Stockden, Minister, dec'd.," and on the west by the Southampton River. The lease is dated 20 September 1628. This appears, at first glance, to be in virtually the same spot as Stockden's 50 acres, as both parcels are bounded on the west by the river and on the south by "Indian Howse Thickett." However,Windmill's lease is bounded on the north by Stockden's land.

The next lease after Windmill's is that of Walter Heyley (also Ely or Heley), who, according to the patent, was an "Ancient Planter." While Heley was not on the list of ancient planters compiled by Nugent in Cavaliers and Pioneers, he was listed as a resident of the east side of the Hampton River in the 1625 muster. His lease, made on the same day as Windmill's, was for 50 acres abutting south on the land of Jonas Stockden, and north toward the head of the river. The east and west boundaries are not mentioned.

Two months later, Windmill was granted another lease, this time of 50 acres, which bounded south on a creek going towards the land of Walter Heley, west on the Southampton River, and east on the main land. This may be the land upon which 44HT55 was located (see Figure 3).

Christopher Windmill came to Virginia in the Bona Nova in 1619. In 1625, when the muster was taken, he was 26 years old, attached to the household of John Ward, and living on the east side of the river. By 1632 Windmill had died and his wife inherited the lease which was promptly conveyed to Francis Hough, her new husband. Hough assigned the northern parcel of Windmill's land to Joseph Hatfield in October 1632, and the southern 60 acres to Henry Coleman in January of 1633 for unknown considerations. Hatfield, ironically, had come to Virginia in 1619 on the Bona Nova with Christopher Windmill, and lived on the east side of the river in 1625 attached to Sgt. William Barry.

The 50-acre parcel leased by Hatfield in 1632 was apparently part of a 116-acre tract patented by Henry Poole on October 17, 1642. The tract included land "previously leased," bounded on the west by the Hampton River, on the south by the Glebe, and on the north by Henry Coleman. The Glebe Land is thought to be part of the old 50 acres leased to the Reverend Jonas Stockden in 1627, and includes the site of the so-called second church (McCartney 1983). By this time Coleman, to the north, had acquired the land originally leased to Walter Heley. Henry Poole sold the whole 116-acre parcel to Richard Hull on October 15, 1655. It was not long after that date that site HT55 was abandoned.

The approach taken to the settling of the Hampton area during the first half of the seventeenth century was obviously a bit different than that of the hinterlands, where leases and patents of over 1000 acres were common. It was different, too, from the Jamestown area, where leases and patents at the time were seldom in excess of a few acres and often less than one (Nugent 1979). This is evidence that Hampton was neither a town nor a particularly rural area, but a dispersed system of small land holdings. Even today, the cities of Hampton, Newport News, and Norfolk are more sprawling than cities such as Richmond, with relatively small, sometimes undiscernible downtown areas.

B. Prehistoric Context

People first inhabited the Peninsula of Virginia approximately 12,000 years ago, toward the end of the Late Pleistocene. From roughly 10,000 to 8,000 B.C., referred to as the Paleo-Indian Period, Native American populations were adapted to a regional environment different from that of today, a result of cooler climatic conditions still affected by the last of the "Ice Age" glaciers. Few material remains of these people have been found on the Peninsula, and our knowledge of their lifeways comes primarily from archaeological survey and excavation conducted elsewhere in Virginia and in other parts of North America. More mobile than later inhabitants of the region, the Paleo-Indians' primary means of subsistence was the hunting of larger game animals supplemented by general foraging for plant foods.

As climate warmed during the Holocene, the regional environment changed to approximate more modern conditions. The archaeological record provides evidence for a change in cultural adaptations during this period, to an environment increasingly characterized by deciduous forest growth and more pronounced seasonality in the availability of resources. While hunting still played a major role in subsistence, Native American populations made increasing use of plant resources. Sites from the Archaic Period, roughly dated from 8000 to 2000 B.C., are found in a wider variety of environmental settings than previously, but settlement systems were still characterized by a high degree of residential mobility.

The archaeological record for the next three thousand years, 2000 B.C. to A.D. 1000, is remarkably different. As discussed in Chapter 1, the Woodland I Period is characterized by the development of intensive riverine and estuarine adaptations and increased residential permanency by larger group aggregates. Several regional syntheses have addressed the archaeological record of this period (Custer 1984, 1989; Gardner 1980). Locally, however, it is apparent that relatively little work has focused on this period, especially when compared to the amount of historical archaeology accomplished to date on the Peninsula. A listing of relevant projects includes the following investigations, which range from surveys to full-scale excavations:

- Chickahominy River Survey (Barka and McCary 1969)

- York County Survey (Derry et al. n.d.)

- New Quarter Park Survey (V.R.C.A. 1978)

- Kingsmill Survey (Reinhart 1973)

- Second Street Survey (Hunter, Samford, and Brown 1984)

- Governor's Land Survey (Reinhart and Sprinkle n.d.)

- Route 199 Survey (Hunter and Higgins 1985)

- Mulberry Island (Beaudry 1976)

- Oakland Dairy (Mullen, Geier, and McCartney 1980)

- Fort Eustis (Opperman 1984)

- College Creek (Reinhart 1978)

- Powhatan Creek (Reinhart 1976)

- Carter's Grove (Muraca 1989)

- Croaker Landing (Egloff et al. 1988)

- Various York County projects (McCary 1958; Rountree 1967)

- Skiff's Creek (Geier and Barber 1983)

Research on other sites within the Virginia Coastal Plain includes these additional projects:

- Maycock's Point, Prince George County (Barka and McCary 1977; Barber 1981; Opperman 1980)

- White Oak Point, Westmoreland County (Waselkov 1982)

- Chicacoan Locale, Northumberland County (Potter 1982)

- Great Neck, Virginia Beach (Painter 1967, 1979, 1980a, 1980b; Geier 1986; Turner and Egloff 1984)

As reviewed in Colonial Williamsburg's resource protection plan (Hunter and Higgins 1986), this body of research suggests that settlement systems during the Woodland I Period involved residential groupings of two types. These 15 included residential bases occupied by what has been termed the "macroband," a social and economic unit comprised of several families, and those occupied by a subgroup of the larger unit, the "microband," perhaps comprised of a single nuclear or extended family. Both types of base camps are commonly found situated on elevated landforms adjacent to high-productivity riverine or estuarine settings. The archaeological record also includes procurement sites which were occupied for a short period of time while specific activities involved in the utilization of a particular resource were carried out.

While the settlement systems of the Paleo-Indian and Archaic Periods were also characterized by the fission and fusion of population groups, the residential bases dating from the Woodland I Period suggest a higher degree of sedentism. Evidence of structures and large pits, possibly used for the storage of plant foods, has been found at several sites dating from the middle and later years of the period (Custer 1989; Geier 1986; Turner and Egloff 1984). Analysis of faunal assemblages indicates that some sites were occupied for extended periods spanning several seasons (Barber 1981; Whyte 1986). The areal extent of base camps and the extensive midden deposits associated with some of them (Barber 1981; Geier 1986) suggest that the population size of the aggregate units may have been larger than during preceding periods.

The Woodland I Period is also characterized by several changes in the use of food resources. The earliest evidence for the use of shellfish within the region dates to ca. 2000 B.C. (Potter 1982; Waselkov 1982), and shell midden sites are quite common later in the period. Site locations and faunal remains indicate that fishing was also an important subsistence activity. Evidence for changes in the use of plant foods is less direct, since relatively little data on this subject has been accumulated in the region to date. The presence of large pit features at some sites does suggest, however, that certain plant foods were harvested intensively at levels sufficient to enable them to be stored for later use.

While plant foods included mast crops such as hickory nuts, walnuts, and acorns, which were also important during earlier times, research in the Southeast indicates that a variety of starchy and oily seed plants were beginning to be cultivated as early as the first millennium B.C. (Yarnell and Black 1985). Cultivated plants included types of maygrass, knotweed, and barley little different from wild forms. Cultigens such as bottle gourds and squash, sunflowers, marsh elders, and chenopods were also grown. The best evidence for early corn in the Southeast dates to the fourth century A.D., but this domesticate is not found in abundance until the Missippian Period, when the earliest beans appear (Yarnell and Black 1985). More locally, plant remains of chenopod and knot-weed have been found in fifth century A.D. contexts in Henrico County (Gleach 1985). Corn has been radiocarbon dated to A.D. 1030 ± 75 at the Point of Fork site in Fluvanna County (Mouer 1985) and has been found in several components postdating A.D. 1100 at the White Oak Point site in Westmoreland County (Waselkov 1982:311).

One of the most important and diagnostic technological advances characterizing the Woodland I Period in the Middle Atlantic Region was the introduction of a ceramic container technology. Major trends in the development of prehistoric ceramics in the Virginia Coastal Plain have been summarized by Egloff and Potter (1982). From ca. 2000 B.C. and continuing for a short time into the Early Woodland Period, Native Americans within the Middle Atlantic Region had produced durable containers from steatite (soapstone), a material not indigenous to the Coastal Plain but found in various places in the adjacent Piedmont province. Steatite was carved into round or oval bowl forms with flat bottoms and small lug handles. The earliest ceramic containers manufactured in the region appear ca. 1200 B.C.

These early ceramics were commonly produced in shapes similar to stone bowls, some employing steatite as a tempering agent (Marcey Creek ware) and others employing materials such as crushed schist or grog (Bushnell and Croaker Landing wares). By at least 500 B.C., a sand 16 tempered ceramic tradition in which coil-construction was used to produce concoinal vessels predominated in the Middle Atlantic Region, with types such as Accokeek and Popes Creek ware found in the Virginia Coastal Plain. This tradition was replaced in at least the Outer Coastal Plain with a shell tempered technology by the first or second century A.D. Mockley ware, a shell tempered, cord and knotted net impressed ceramic, predominates in the archaeological record until ca. 900 A.D., after which it was replaced by the shell tempered, fabric marked ceramic type known as Townsend ware.

Remaining aspects of the known material culture of the Woodland I Period include tools and ornaments made of stone, bone, and shell. Diagnostic projectile points for the period include a variety of large stemmed points with narrow blades, broadspears, small points with contracting stems, and large triangulars (Custer 1989). Points commonly associated with Mockley ware ceramics within the Virginia Coastal Plain during the late Woodland I Period include the Potts Corner-Notched and Side-Notched, Fox Creek and Selby Bay, Rossville, and large triangular types (Egloff et al. 1988:14-17; Geier 1983:96-118; McCary 1953; Potter 1982:330).

While research elsewhere within the Middle Atlantic Region has shown that populations at this time were participating in far-reaching exchange networks involving raw lithic materials and finished artifacts (Custer 1984, 1989), there is presently less evidence for this in the Virginia Coastal Plain. Occasionally tools of exotic materials, such as rhyolite, are found, but lithic assemblages are dominated by quartz and quartzite which are available locally. In the far Outer Coastal Plain of Virginia where large cobbles of quartz and quartzite are not accessible, tools were fashioned from small pebbles of local jasper, and bone seems to have replaced the use of stone for many items (Geier 1986; Painter 1980a). Tools and ornaments fashioned from bone and antler included projectile points, awls, flakers, cups, and decorated pins (Painter 1980a; Potter 1982:276-330; Turner and Egloff 1984).

Mortuary patterns characteristic of Woodland I populations are not well understood for the Virginia Coastal Plain, since few burials have been discovered, and those excavated have been poorly reported on. Thus far, there is no evidence of complex mortuary centers such as those associated with the Delmarva Adena Complex or that found at the Island Field site in Delaware (Custer 1984, 1989). Excavations by James Madison University at the Great Neck site in Virginia Beach uncovered two possible Woodland I Period burials. One burial contained the primary inhumation of a single individual, while the other held several disarticulated fragments of human longbone. The former was placed in a semi-flexed position within an oval pit with sloped walls measuring 4.1 by over 1.6 feet. The disarticulated remains were contained within a roughly rectangular pit, 3.0 by 2.3 feet in plan and over 0.8 feet deep, and appeared to be interred along with trash deposits (Geier, Cromwell, and Hensley 1986:85-91). At the Currituck site in coastal North Carolina, dated ca. 800-600 B.C., Painter has found a variety of burial types including individual and mass primary interments, along with secondary bundle burials (Painter 1977).

Chapter 5.

The Prehistoric Sites

A. Site 44HT36

The presence of site 44HT36 (Photo 2) was first indicated during the Phase I and II testing carried out by the Tidewater Cultural Resource Center of the College of William and Mary during the summer of 1987. Test units placed in the University's R.O.T.C. parade ground revealed a minor concentration of aboriginal ceramics and several associated features. A 108by-66 foot area in the northwestern section of the parade ground was stripped of sod, late topsoil, and plowzone, revealing a total of 55 features containing prehistoric or historic deposits (Figure 4). The prehistoric and historic components of the site are summarized below, with detailed information on selected features provided in the section following.

It should be noted before discussing the features at sites HT36 and HT37 that both sites were characterized by a very sandy subsoil. Because of this substrate, excavated dimensions of features may not truly represent the original dimensions of pits. It is likely that feature walls have slumped and organics within the fill have migrated into the surrounding matrix. This characteristic of the sites also made it difficult to determine whether some features were prehistoric pits or natural tree holes.

Prehistoric features at 44HT36 are somewhat scattered across the excavation area opened at the site, not displaying the tighter clustering seen at site 44HT37. Those features most clearly identified as dating from the prehistoric period are distributed within an area defined north-south by grid lines S90 and S150 and east-west by grid lines E30 and E60 (see Table 1).

At the northern end of this area, at least four prehistoric pit features were identified. The largest of these was Feature 42/47/48/122, which measured 4.7' in diameter and 3.8' deep. Charcoal derived from the bottom layer of the pit yielded a radiocarbon date of A.D. 20 ± 70 years. Situated within twenty feet west of Feature 42 were three smaller pits. Features 13/14 and 4/5/6 were roughly 3.0' in diameter and 1.5' deep. Still smaller was a fourth prehistoric pit, Feature 38/40/41, which was located adjacent to Feature 13/14. The fill of each of these four features contained a number of prehistoric artifacts, primarily ceramic sherds, while the second layer in Feature 38/40/41 also contained bits of shell.

The remaining features at 44HT36 positively identified as dating from the prehistoric period were located thirty to forty feet south of those discussed above. Feature 71 was 2.75' in diameter and 2.7' deep. Feature 19/20 was a shallower, oval pit measuring 2.6' by 1.1' in plan and extending to a depth of 1.2' below subsoil level.

If only the features discussed above are considered prehistoric, the archaeological remains within the excavated area of 44HT36 suggest perhaps two non-contemporaneous encampments occupied by small groups of people. There were several other features uncovered at the site which are of possible prehistoric origin, however (these are discussed in greater detail below). If these features are indeed prehistoric, interpretation of the prehistoric occupation at 44HT36 is made more difficult. Given the present capabilities of archaeology, it is impossible to determine if the complex of prehistoric features represents one large encampment or several noncontemporaneous ones. The rather small number of artifacts recovered in the excavation would suggest, however, that the latter interpretation is the correct one.

The archaeological evidence also suggests that prehistoric remains at 44HT36 are representative of a semi-sedentary population. While no structural remains were discovered, the size of some of the pit features would be compatible with

18

Photo 2. Aerial view of 44HT36.

their use as storage facilities. Therefore, it is likely that the encampments established here were either occupied throughout one or more seasons or were used as caching areas to be returned to at a later time. The vast majority of ceramics recovered

from across the excavation area are shell tempered, cord and knotted net impressed, indicating the site was used during the late Woodland I Period. The radiocarbon date of A.D. 20 (± 70) derived from charcoal in Feature 42 confirms this affiliation.

Photo 2. Aerial view of 44HT36.

their use as storage facilities. Therefore, it is likely that the encampments established here were either occupied throughout one or more seasons or were used as caching areas to be returned to at a later time. The vast majority of ceramics recovered

from across the excavation area are shell tempered, cord and knotted net impressed, indicating the site was used during the late Woodland I Period. The radiocarbon date of A.D. 20 (± 70) derived from charcoal in Feature 42 confirms this affiliation.

Historic-period occupation of site 44HT36 is represented primarily by post hole features. A total of 21 historic post holes were positively identified within the excavation area, none of which appears to define a structure. Eight post holes,

however, comprise a prominent fenceline, probably erected no earlier than the mid-nineteenth century, when the area was part of Tabb Farm. The fence runs north-south along grid line E60 and includes the following features (listed from north to south): Features 142, 1/2, 10/11, 16/17, 107, 105, 127/129, 133, and possibly 102/103 (not mapped). Several other post holes were located

within a ten-foot radius of grid point S160 E60, including Features 102/103, 127/129, 132,

19

Figure 4. Overall drawing of 44HT36.

134, 135, 136, 137, and 140. At the northern end of the excavation area, three larger post holes were found: Features 64/66, 94/96, and 98/100. Two additional post holes, Feature 111/112 and 114, were identified in the excavation area west of the ROTC Road.

Figure 4. Overall drawing of 44HT36.

134, 135, 136, 137, and 140. At the northern end of the excavation area, three larger post holes were found: Features 64/66, 94/96, and 98/100. Two additional post holes, Feature 111/112 and 114, were identified in the excavation area west of the ROTC Road.

In addition to post holes, two other historic features were identified at 44HT36. Feature 73, located in grid unit S90 E90, was a large, somewhat oval pit, 4.0' long, 2.1' wide, and 0.6' deep with very straight walls and a flat bottom. Both prehistoric and historic artifacts were contained in the fill. Feature 33/36/37, located in grid unit S110 E40, is also suspected to date from the historic period. Although the feature fill yielded only one fragment of fire-cracked rock, the pit is rectangular in plan and profile, and roughly the same size and shape as Feature 73.

For a number of the remaining features uncovered during excavations at 44HT36, it could not be positively determined whether they dated from the prehistoric or historic period. Most of the features were relatively small, shallow pits containing one layer of fill and yielding few or no artifacts. Among the features located at the northern end of the excavation area fitting this description were at least two, Features 60 and 62, whose placement strongly suggests that they represent historic post holes. In cross-section, both have very straight sides, with flat bottoms at a depth of 0.5' below subsoil level. These features also lie roughly in line with Features 64/66 and 98/100, known historic post holes, and both are situated at a similar distance from post hole 64/66. Other features of somewhat similar shape and size situated at the northern end of the excavations area include Features 25, 26/30, 27, 49, 52, and 69. These pits range in size from 1.5 to 2.5' in diameter and vary in depth from 0.5 to 0.9' below subsoil level. Few contained any artifacts, and, with the exception of Feature 26/30, all contained only one discernible layer of fill.

Features 34 and 51 may also represent historic post holes. Both contained small depressions at the center of their bases. In Feature 34, this depression strongly suggests the seating for a post. The evidence for Feature 51 is less clear; it is larger than Feature 34 and contained a number of burned prehistoric ceramic sherds. Features 34 and 51 do lie roughly in line with a post hole, Feature 140, at the southern end of the excavation area, however. A line drawn connecting the three would lie parallel to the prominent historic fence line running through the excavation area along grid line E60.

Features at the southern end of the excavation area for which cultural affiliation is uncertain include Features 8, 43/45, and 76. Ranging in size from 1.9 to 2.5' in diameter and in depth from 1.1 to 1.8' deep, these pits could represent historic post holes. Feature 43/45 contained several prehistoric sherds in Layer 43, an orange sandy fill. Layer 45, a core of dark brown sandy loam containing charcoal, somewhat suggests the remains of a burned post. Features 8 and 67 contained only one layer of fill yielding no artifacts. The cultural affiliation of a somewhat larger pit, Feature 116, located in the western section of the site, is also uncertain.

Several non-cultural features were also identified within the excavation area at 44HT36. The following features most likely represent filled tree holes: Features 22, 46, 77, 79/81, 86/90, 88, 120/123, 124/126. The fill of three of these disturbances, Features 46, 79/81, and 120/123, contained small amounts of prehistoric debris.

Description of Features

Feature 4/5/6 (see Figure 5) was a roughly circular pit measuring 3.1' by 3.3'in plan and extending 1.7' below subsoil level. The walls of the feature were relatively straight sided and the base gently rounded. Three layers of fill could be discerned within the feature.

Layer 4, the uppermost deposit, consisted of brown sandy loam with some charcoal inclusions and was about 1.0' thick. This layer contained the vast majority of artifacts recovered from the feature. Included were 42 shell tempered sherds: 22 cord marked, 18 knotted net impressed, 1 plain surfaced, and 1 unidentified. A minimum of

21

Figure 5. Feature section drawings—44HT36.

22

five vessels are represented in the assemblage: 3 cord marked and 2 knotted net impressed. Four highly-weathered sherds were also recovered. The layer also contained a fired coil of a fine, sandy paste ceramic, 1 quartzite flake, 1 quartzite mano,

4 fire-cracked rocks, and a quartzite cobble. One seed identified to Gramineae (Grass family) was also recovered.

Figure 5. Feature section drawings—44HT36.

22

five vessels are represented in the assemblage: 3 cord marked and 2 knotted net impressed. Four highly-weathered sherds were also recovered. The layer also contained a fired coil of a fine, sandy paste ceramic, 1 quartzite flake, 1 quartzite mano,

4 fire-cracked rocks, and a quartzite cobble. One seed identified to Gramineae (Grass family) was also recovered.

Layer 5 was the second layer of fill in the pit, consisting of about 0.4' of light brown sandy silt mounded slightly higher in the center of the feature. The layer contained 4 sherds, all shell tempered: 3 knotted net impressed and one cord marked.

The bottom layer of the pit, Layer 6, consisted of tan sandy clay about 0.3' thick. Included among the fill were 3 shell tempered sherds: 2 knotted net impressed and 1 plain. One small fragment of quartzite with water-worn surfaces was also recovered.

Feature 7 was an oval pit, 2.0' by 1.5'. The feature had steeply sloping sides extending to a nearly pointed bottom 1.8' below subsoil level. Fill consisted of greyish-brown sandy loam which contained no artifacts.

Feature 13/14 (see Figure 5) was a circular pit 3.0' in diameter and 1.3' deep with sloping sides and a flat bottom. The upper layer of the feature, Layer 13, extended to 0.7' below subsoil and was filled with brown sandy loam. The layer yielded 9 shell tempered sherds: 6 cord marked, 2 knotted net impressed, and 1 unidentified, representing a minimum of three vessels. Three quartzite flakes were also recovered. The bottom of the feature was filled with a pale brown sandy clay which contained no artifacts. Layer 14 was 0.6' thick.

Feature 19/20 (see Figure 5) was a roughly ovate pit measuring 2.6' by 1.1'. The walls sloped abruptly to a flat bottom 1.2' below subsoil. The main feature, represented by Layer 20, was filled with mottled orange clay containing charcoal flecks but no artifacts. Artifacts were recovered from a pocket of fill, Layer 19, lying at the east end of the pit. Approximately 1.0' in diameter and 1.0' deep, Layer 19 consisted of dark grey-brown loam. Three sherds of shell tempered, cord marked ceramic representing one vessel were contained in the fill.